The Complexity Triad

Disclosure: This site may contain links to affiliate sites that earn me a small commission at no additional cost to you. Please know that I only recommend products and services that I personally use!

It’s no secret that I tend to collect the odd duck students, those with non-standard Agility breeds, or who’s greatest struggles are arousal, confidence, and drive. I love teaching these students; the challenge they present forces me to think critically about each exercise and it’s success criteria, then to continually reflect back on how well our results align with that criteria. With that in mind, I’ve been thinking a lot lately about the link between strategic, intentional training practices (or lack there of) and frustration behaviors in our dogs. For many of these students, you have one shot to get it right. Your marker mechanics need to be on point, your reward placement needs to be perfect, and the exercise needs to be intentionally designed to set the dog up for success. If you’ve ever worked with me, you’ve heard me say that I expect a 95% success rate in any exercise; from weave poles to sequencing, I want to keep my reinforcement rate high and not allow my dog to practice the wrong behavior. But many of us fall into the trap of over-facing our dogs, and next thing we know it’s been a full training session with no reinforcement in sight. This will eventually lead to frustration behaviors and either over or under-arousal, causing barking, spinning, biting, or sniffing and checking out.

So how can we ensure that we achieve a 95% successful rate? How do we keep our training sessions short and efficient, and keep our dogs happy and engaged?

We need a model to help break our exercises down into their component pieces, which leads me to the complexity triad.

The Complexity Triad

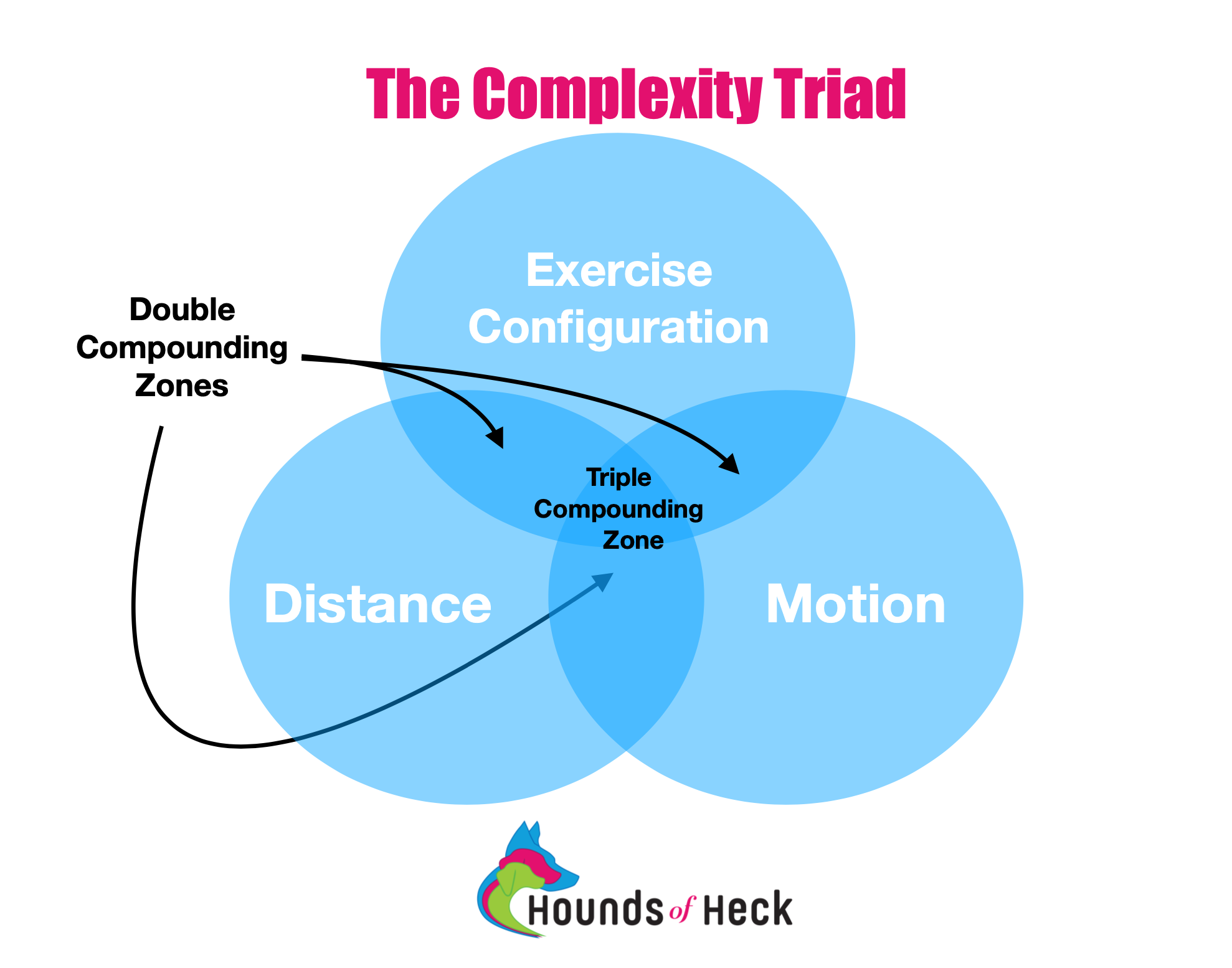

In any Agility exercise, there are 3 ways we can change the challenges presented to our dogs (see image):

1.Exercise Configuration: altering the specific layout of the exercise

You can think of this piece of the triad as having to do with some change to the equipment configuration itself. If, for example, we are training channel weaves, we can close the gap between the poles slightly. If we are practicing front crosses, we can change the angle and layout of the jumps. By changing an element of the equipment configuration, we can manipulate an exercise to make it harder or easier.

2. Motion: both handler and dog specific motion

We can add either handler or dog specific motion to an exercise to increase or decrease the complexity. For example, we can increase the handler’s speed past a dog walk to increase the difficulty of training contact criteria. Similarly, we can change the dog’s speed on approach to the dog walk to change the difficulty of maintaining criteria. Generally, more motion means more difficulty, but there are a few cases where adding motion can decrease the difficulty (for instance sending ahead to a jump with forward motion from both dog and handler is easier than with a static send).

3. Distance: both handler and dog specific distance

As we add distance to any exercise it becomes more difficult. For example, a dog may be able to send 10’ ahead to a jump, but a 15’ send is much more difficult. Similarly, the dog may be able to handle a 15’ send ahead, but if the handler is lateral instead of behind, the dog may have more difficulty. As these examples show, in addition to dog distance and handler distance, there are a few types (or directionalities) that we need to remember as well (lateral distance, distance ahead, distance behind, etc.).

Using the Triad

In practice, the triad can be applied to any Agility exercise. Whether you are training obstacle skills like contacts and weaves, or sequencing, the triad still holds true. It also provides you with a structure to critically evaluate your training practices, and to pick your battles so that you are intentionally training the component you set out to train, and don’t get sucked into a side challenge.

When I set my training plan for the day, I'll pick a particular exercise, then pick one component of the triad to work on. For instance, if I’m training channel weaves, I may choose to only focus on closing the poles. This means I’m working on the Exercise Configuration component, so for each repetition I will only change that element. I won’t change the dog’s distance to the channels. I won’t change my motion or handling. Every repetition will look exactly the same, except that I will slowly change how widely spaced the channels are.

In a different session, I may choose to proof lateral distance from the channel weaves. In that case, I select an exercise configuration where I know my dog will be successful (for instance leaving the channels open so I don’t have to worry about skipped poles). I then keep the dog’s speed and distance into the poles constant from repetition to repetition by using the same set up point, but will vary how much lateral distance I have from the weave poles. To do this, I’ll set cones as a visual reference point (think gamble line) and handle the weaves from beyond the cones.

By using the triad in this way, I help to control some of the variables. How many times have you tried to work a hard weave pole entry, but accidentally got too far ahead and the dog popped at pole 10? What do you do in that case? How do you reward? Your dog nailed the entry (which was your training goal), but you don’t want to reinforce the pop. Through use of the triad, I set myself, and my dog up for success by ensuring that I don’t accidentally introduce a complexity element into an exercise.

Compounding Zones

Now you may be thinking “that’s nice, but in a trial I can’t control each of those elements individually” and you’re absolutely correct! That’s where the compounding zones come in (see diagram). Once I have successfully trained every variation of each aspect of the triad individually, I begin compounding two aspects of the triad.

If we stick with our channel weaves example from above, this means I may train closed poles with lateral motion. In that case, the dog’s starting point and entry will remain the same. In a different session, I may train the entry with closed poles, but ensure my motion stays the same.

When you’ve worked through each possible scenario of the double compounding zones, then you are finally ready for the triple compound, or training the most difficult exercise configurations with any distance and motion.

Many handlers will stop at the double compounding zones. This is the world of “managing” the skill. Here, the dog may know all the weave pole entries, but the handler can’t be too far laterally. Depending on your goals, that may be fine, but I would argue that true obstacle independence occurs when you have concurred the triple compounding zone.

I regularly use The Complexity Triad in my own training, and in my teaching practices with my students. I’ve recently begun introducing this as a lecture topic in some of my seminars as well. I hope the concept helps you understand how to better break down your training sessions, ensuring success, clarity, and a high reinforcement rate for your dog. You can also use the triad as a sort of training checklist to make sure that your dog truly has all the skills they need to succeed. Take a moment to think about each variation of each component of the triad (i.e. 4 o’clock entries vs. 11 o’clock entries vs. lateral distance vs. sends ahead) and write them all down. Gradually work your way through each component and check them off as you go. We all have comfort zones that we typically fall into, and so often we have multiple dogs that have the same training gaps. Using the triad as a checklist will help to push you outside of your comfort zone and prevent you from recreating those gaps!